Getting started¶

Trying it out¶

While we consider pyMOR mainly as a library for building MOR applications, we

ship a few example scripts. These can be found in the src/pymordemos

directory of the source repository (some are available as Jupyter notebooks in

the notebooks directory). Try launching one of them using the pymor-demo

script:

pymor-demo thermalblock --plot-err --plot-solutions 3 2 3 32

The demo scripts can also be launched directly from the source tree:

./thermalblock.py --plot-err --plot-solutions 3 2 3 32

This will reduce the so called thermal block problem using the reduced basis method with a greedy basis generation algorithm. The thermal block problem consists in solving the stationary heat equation

- ∇ ⋅ [ d(x, μ) ∇ u(x, μ) ] = 1 for x in Ω

u(x, μ) = 0 for x in ∂Ω

on the domain Ω = [0,1]^2 for the unknown u. The domain is partitioned into

XBLOCKS x YBLOCKS blocks (XBLOCKS and YBLOCKS are the first

two arguments to thermalblock.py). The thermal conductivity d(x, μ)

is constant on each block (i,j) with value μ_ij:

(0,1)------------------(1,1)

| | | |

| μ_11 | μ_12 | μ_13 |

| | | |

|---------------------------

| | | |

| μ_21 | μ_22 | μ_23 |

| | | |

(0,0)------------------(1,0)

The real numbers μ_ij form the XBLOCKS x YBLOCKS - dimensional parameter

on which the solution depends.

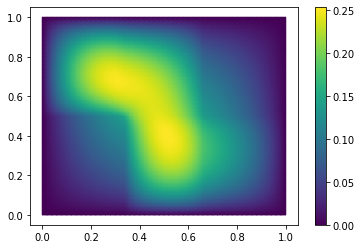

Running thermalblock.py will first produce plots of two detailed

solutions of the problem for different randomly chosen parameters

using linear finite elements. (The size of the grid can be controlled

via the --grid parameter. The randomly chosen parameters will

actually be the same for each run, since a the random generator

is initialized with a fixed default seed in

default_random_state.)

After closing the window, the reduced basis for model order reduction

is generated using a greedy search algorithm with error estimator.

The third parameter SNAPSHOTS of thermalblock.py determines how many

different values per parameter component μ_ij should be considered.

I.e. the parameter training set for basis generation will have the

size SNAPSHOTS^(XBLOCKS x YBLOCKS). After the basis of size 32 (the

last parameter) has been computed, the quality of the obtained reduced model

(on the 32-dimensional reduced basis space) is evaluated by comparing the

solutions of the reduced and detailed models for new, randomly chosen

parameter values. Finally, plots of the detailed and reduced solutions, as well

as the difference between the two, are displayed for the random

parameter values which maximises reduction error.

The thermalblock demo explained¶

In the following we will walk through the thermal block demo step by

step in an interactive Python shell. We assume that you are familiar

with the reduced basis method and that you know the basics of

Python programming as well as working

with NumPy. (Note that our code will differ a bit from

thermalblock.py as we will hardcode the various options the script

offers and leave out some features.)

First, start a Python shell. We recommend using IPython

ipython

You can paste the following input lines starting with >>> by copying

them to the system clipboard and then executing

%paste

inside the IPython shell.

First, we will import the most commonly used methods and classes of pyMOR by executing:

from pymor.basic import *

from pymor.core.logger import set_log_levels

set_log_levels({'pymor.algorithms.greedy': 'ERROR', 'pymor.algorithms.gram_schmidt.gram_schmidt': 'ERROR', 'pymor.algorithms.image.estimate_image_hierarchical': 'ERROR'})

Next we will instantiate a class describing the analytical problem

we want so solve. In this case, a

thermal_block_problem:

p = thermal_block_problem(num_blocks=(3, 2))

We want to discretize this problem using the finite element method.

We could do this by hand, creating a Grid, instatiating

DiffusionOperatorP1 finite element diffusion

operators for each subblock of the domain, forming a LincombOperator

to represent the affine decomposition, instantiating a

L2ProductFunctionalP1 as right hand side, and

putting it all together into a StationaryModel. However, since

thermal_block_problem returns

a StationaryProblem, we can use

a predifined discretizer to do the work for us. In this case, we use

discretize_stationary_cg:

fom, fom_data = discretize_stationary_cg(p, diameter=1./50.)

fom is the StationaryModel which has been created for us,

whereas fom_data contains some additional data, in particular the Grid

and the BoundaryInfo which have been created during discretization. We

can have a look at the grid,

print(fom_data['grid'])

Tria-Grid on domain [0,1] x [0,1]

x0-intervals: 50, x1-intervals: 50

elements: 10000, edges: 15100, vertices: 5101

and, as always, we can display its class documentation using

help(fom_data['grid']).

Let’s solve the thermal block problem and visualize the solution:

U = fom.solve([1.0, 0.1, 0.3, 0.1, 0.2, 1.0])

fom.visualize(U, title='Solution')

Each class in pyMOR that describes a Parameter-dependent mathematical

object, like the StationaryModel in our case, derives from

ParametricObject. ParametricObjects automatically determine the

Parameters they depend on from ParametricObjects that have been passed

as __init__ arguments and from the

parameters_own and

parameters_internal

attributes that have been set in __init__.

Let’s have a look:

print(fom.parameters)

{diffusion: 6}

This tells us, that the Parameters which

solve expects

should be a dictionary with one key 'diffusion' whose value is a one-dimensional

NumPy array of size 6, corresponding to the block structure of

the problem. However, as an exception to this rule, the interface methods of

Models allow simply passing the list [1.0, 0.1, 0.3, 0.1, 0.2, 1.0] by

internally calling parse.

Next we want to use the greedy algorithm

to reduce the problem. For this we need to choose a reductor which will keep

track of the reduced basis and perform the actual RB-projection. We will use

CoerciveRBReductor, which will

also assemble an error estimator to estimate the reduction error. This

will significantly speed up the basis generation, as we will only need to

solve the high-dimensional problem for those parameters in the training set

which are actually selected for basis extension. To control the condition of

the reduced system matrix, we must ensure that the generated basis is

orthonormal w.r.t. the H1_0-product on the solution space. For this we pass

the h1_0_semi_product attribute of the model as inner product to

the reductor, which will also use it for computing the Riesz representatives

required for error estimation. Moreover, we have to provide

the reductor with a ParameterFunctional which computes a lower bound for

the coercivity of the problem for given parameter values.

reductor = CoerciveRBReductor(

fom,

product=fom.h1_0_semi_product,

coercivity_estimator=ExpressionParameterFunctional('min(diffusion)', fom.parameters)

)

Moreover, we need to select a training set of parameter values. The problem

p already comes with a ParameterSpace, from which we can easily sample

these values. E.g.:

training_set = p.parameter_space.sample_uniformly(4)

print(training_set[0])

{diffusion: [0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1]}

Now we start the basis generation:

greedy_data = rb_greedy(fom, reductor, training_set, max_extensions=32)

The max_extensions parameter defines how many basis vectors we want to

obtain. greedy_data is a dictionary containing various data that has

been generated during the run of the algorithm:

print(greedy_data.keys())

dict_keys(['max_errs', 'max_err_mus', 'extensions', 'time', 'rom'])

The most important items is 'rom' which holds the reduced Model

obtained from applying our reductor with the final reduced basis.

rom = greedy_data['rom']

All vectors in pyMOR are stored in so called VectorArrays. For example

the solution U computed above is given as a VectorArray of length 1.

For the reduced basis we have:

RB = reductor.bases['RB']

print(type(RB))

print(len(RB))

print(RB.dim)

<class 'pymor.vectorarrays.numpy.NumpyVectorArray'>

32

5101

Let us check if the reduced basis really is orthonormal with respect to

the H1-product. For this we use the gramian

method:

import numpy as np

gram_matrix = RB.gramian(fom.h1_0_semi_product)

print(np.max(np.abs(gram_matrix - np.eye(32))))

2.4302825377131576e-14

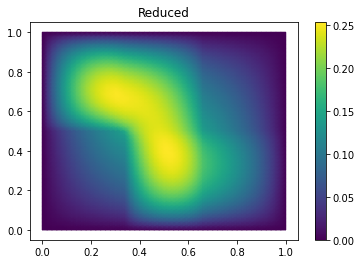

Looks good! We can now solve the reduced model for the same parameter values

as above. The result is a vector of coefficients w.r.t. the reduced basis, which is

currently stored in RB. To form the linear combination, we can use the

reconstruct method of the reductor:

u = rom.solve([1.0, 0.1, 0.3, 0.1, 0.2, 1.0])

print(u)

U_red = reductor.reconstruct(u)

print(U_red.dim)

[[ 0.56008169 0.19410562 0.00463453 0.01675562 0.04900982 0.07760119

-0.08043888 -0.02889488 -0.03121126 0.26467367 0.13991773 -0.09805741

0.16005484 0.04417512 -0.05245844 -0.00132281 -0.01304436 0.01330245

-0.02185056 0.00625769 -0.00868736 -0.00115484 0.01895446 -0.00153234

0.02306277 0.0035532 0.01061803 -0.00225572 0.00199581 -0.0068476

0.00186538 0.0047302 ]]

5101

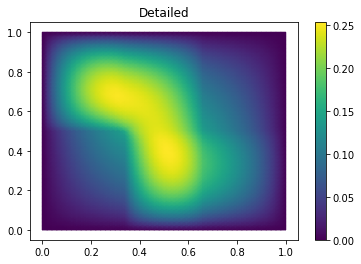

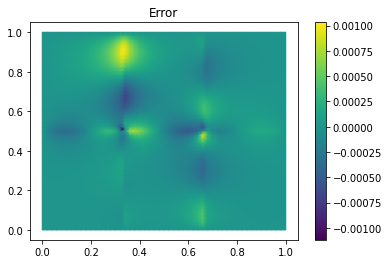

Finally we compute the reduction error and display the reduced solution along with the detailed solution and the error:

ERR = U - U_red

print(ERR.norm(fom.h1_0_semi_product))

fom.visualize((U, U_red, ERR),

legend=('Detailed', 'Reduced', 'Error'),

separate_colorbars=True)

[0.00480011]

We can nicely observe that, as expected, the error is maximized along the jumps of the diffusion coefficient.

Download the code: getting_started.py getting_started.ipynb

Learning more¶

As a next step, you should read our Technical Overview which discusses the most important concepts and design decisions behind pyMOR. You can also follow our growing set of pyMOR Tutorials, which focus on specific aspects of pyMOR.

Should you have any problems regarding pyMOR, questions or feature requests, do not hesitate to contact us at our mailing list!